Unlike so many others, both Eduard Tubin and his younger compatriot Evi Liivak survived the disaster of the second World War. Their lives and careers, however, were irrevocably affected in ways that cannot be known. Miss Liivak, trapped in Germany during the war, confined her recitals to underground affairs for Estonian refugee groups until the war ended. Eventually she lived in New York City and performed in many countries, yet struggled to regain the prestige and support in her new country that she had earned in Estonia before being forced to flee by the Nazis’ murder of her father.

Eduard Tubin managed to remain and work in his country during the first Soviet occupation and that of the Germans, but life became so difficult, dangerous, and restrictive that as the Soviets arrived for the second time, he and thousands of others fled in panic. Not without reason: the Soviets almost immediately sent thousands to Siberia, killed other thousands outright, and locked Estonia behind the Iron Curtain for almost forty years. In Estonia Tubin had been a recognized and appreciated conductor and composer. In Sweden, there was the challenge of how to re-establish his career and achieve recognition in a new country, as well as to solve the universal refugee problems of money, housing, language, loss of professional and personal relationships, and social acceptance.

As musicians and members of the Estonian diaspora, over the following decades Eduard Tubin and Evi Liivak would have known, or at the very least known about, each other. Miss Liivak often programmed works by Tubin, as well as by Eller and Lemba. They each participated in Estonian events and festivals, of which a number were international in scope. Already in a 1949 letter to violist and conductor Endel Kalam, who was then still in Germany, he says that “E. Liivak has my Capriccio, which I wrote before (i.e. in Estonia), maybe you can get it from her, since I don’t have it anymore.” When he eventually recovered the Capriccio, he made some revisions. Vardo Rumessen, the pianist and compiler of the complete catalog of Tubin’s works, notes in his book that Evi Liivak played the Capriccio No. 1 from 1948 on. So it is a great joy that a work by Eduard Tubin has been included in the second CD of this series in recognition of Miss Liivak’s musical and ethnic heritage.

Early Life

Tubin was born on June 18, 1905 in the village of Torila, Tartumaa County, Estonia, which was then a province of the Russian empire. He was the youngest child of Joosep Tubbin and Sohvi Tehvan. One sibling died in infancy, and his older brother, a schoolteacher, of tuberculosis at 22. The family first lived near the shores of Lake Peipus, one of the largest freshwater lakes of Europe, then moved a few miles inland, renting half of their teacher son’s school and running its farm. Eduard’s father was a fisherman and tailor, and soon a farmer. His hobby was playing trombone, sometimes trumpet and even tuba in the local orchestra. The composer’s mother loved to sing both folk tunes and hymns.

After two years at his brother’s school, Eduard began to board at the local Torila County elementary school some miles distant. There he also took part in the farm work of the village. His summer job was to herd the village pigs, for which he carried along the piccolo flute and scores that he had inherited from his brother. His son quotes the composer: “It’s perhaps peculiar that I always carried my flute and scores with me when ‘I worked’ looking after the pigs. I had dance tunes, even violin concertos that I borrowed from the violinist in the orchestra. The pigs were grazing and the swineherd played technical passages by Viotti, Rode and other such masters as accompaniment.” Tubin said that his first listeners, the pigs, were quite smart and seemed to enjoy the flute. All his life he retained a love of animals and nature.

He joined the Koosa village orchestra at age nine. His father encouraged his son’s musical interests, although his mother remained unconvinced about the career prospects. When Eduard was 13, his father sold a calf in Tartu and bought a table piano, which Eduard taught himself to play. Soon he accompanied local and visiting fiddlers.

Tartu and Eller

In 1920, as Estonia established its independence after centuries of occupation by Danes, Poles, Germans, Swedes, and Russians, higher schools of music opened in Tartu and Tallinn. Eduard went to Tartu, then the cultural capitol of Estonia, to study that same year. He was 15. Bending to the will of his parents, he enrolled at the teachers’ college instead of the music school. He remained for six years and graduated, but his interest in music was so strong that after four years he enrolled simultaneously at the Tartu Higher Music School. He earned a place with the important teacher and composer Heino Eller to study music theory and harmony, and later composition.

Eller had a great and lasting influence on Tubin. Even before enrolling in his class, he heard an Eller prelude and later wrote: “. . . you gave me a lesson in the strength of inner force in music and showed me the path . . . to find the force and to know how to use it.” The year after graduation from the teacher’s college, he entered Eller’s class in composition, while also working his required three years as a teacher in a nearby village. Other students in the class included Eduard Oja, Olav Roots, and Karl Leichter.

Eller was a friendly yet exacting teacher. His students studied the techniques of Bach and Palestrina as well as analyzing new music: Ravel, Stravinsky, Bartok, Prokofiev. Years later, in honor of Eller’s 80th birthday, Tubin wrote “. . . I must confess that it was the most profound working time I have ever had in my life. The tasks . . . had to be finished without errors; they had to be logical, well considered and polished . . . anything muddled or diffuse had to be reworked.” Eller also encouraged experimentation; as long as the student worked with full commitment, he would assist. He encouraged his students to explore modern paths in music, and the crystalline focus of Tubin’s compositions was influenced by Eller’s teaching: “. . . he didn’t like much empty talk. You had to say at once what you wanted.” The two men remained in contact for life, discussing composition problems as colleagues.

After graduating from teacher’s college, Eduard spent the summer in the town of Elva with his friend Oja. They supported themselves playing piano and violin together at the local cinema, playing for nine hours straight on movie days. While still teaching in the village, he was offered the job of conductor of the Male Choir Society in Tartu, the cultural capitol of Estonia, and soon raised it to one of the best choirs in the country. He led the choir until 1944. During this period, Tubin wrote songs, piano music, and a first orchestral work, Estonian Folk Dances. In accordance with the Estonian love of song, many of his earliest compositions were based on poetry. As his graduation piece, he wrote a piano quartet.

Vanemuine and the 30s. The Coming of War

In 1930 Tubin graduated from the Tartu Higher School of Music, quit school teaching and moved to Tartu. Within a year, he was the full time conductor of the Vanemuine theater orchestra, working with the head conductor Juhan Simm, and remained there until he fled Estonia in 1944. At Vanemuine, he presented over forty new operas, operettas and ballets, conducted symphony concerts, garden concerts, and took the ensemble on tour. He conducted a number of choirs, and was commissioned to write stage music for plays. His conducting experience became extensive and helpful to his composing. Later, in Sweden, some conductors had difficulty with his complicated rhythms. Orchestra members, on the other hand, liked working with him and enjoyed the challenging solos that he always included. He was so busy at Vanemuine that his own composing was mostly done in the summers. Major works were born: The Suite on Estonian Motifs, Three Pieces for Violin and Piano, the first and second symphonies; and many others. Olav Roots conducted the first performance of the Symphony No. 1 at the Estonia hall in Tallinn, in 1936.

Symphony No. 2, Legendary, was performed in 1938, conducted by Olav Roots. Some critics complained of density of sound and disharmonies. But in 1984, a Swedish critic said he wept in his seat at the “formally perfect and enormously expressive music,” hearing in it “something of an instrumental requiem from a Europe on the brink of disaster.”

A marriage of several years in the 30s produced a son, Rein. His wife, an actress, appeared in several of the Vanemuine productions. The couple later drifted apart, and he gradually began a relationship with Elfriede Erika Saarik, a ballet dancer in Tartu. They married in 1941, and became the parents of Eino Tubin.

Occupations

As war loomed in 1939, cultural life was still flourishing, but occupation, misery and war were approaching in gradual steps. By September, Estonia was forced to accept a pact with the Soviet union that saw censorship imposed and telegraphic links with other countries cut. 25,000 soldiers rolled into Estonia and established bases. Nine months later, Stalin demanded full military occupation. The next day 100,000 troops crossed the border. By July, 1940, the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic had been incorporated into the Soviet Union. The only free country to recognize the occupation was Sweden, a decision that later haunted Estonian refugees. In Estonia, the dismemberment of society began.

Early in the occupation, things for the composer seemed to go well enough. He was appointed head of the composition class at the Tartu Higher Music School, named chief conductor of the Vanemuine, received commissions for new works, and was one of a group selected for a cultural visit to Leningrad. He was on the committee to establish a new Soviet Estonian Composers’ Union. His son writes that he began that work with naive enthusiasm.

Soon peoples’ main concerns became food, fuel and clothing. Opera, ballet, music and theater were increasingly important to keep their spirits up, and the Vanemuine was busy. The ballet Kratt occupied Tubin; his first ballet, and groundbreaking in Estonia, it was based entirely on folklore and folk music. The score for a second ballet, Wonderbird, was burned when the Estonia theater was bombed in 1944.

The demon Kratt was a dramatic folkloric figure, perhaps based on a natural disaster of 660 BC when fiery meteorites streaked across the sky and crashed into the island of Saaremaa with immense destructive energy. Kratt was described as a figure with a fiery tail flying through the sky who brought riches to its owner. Survivors of the original event found high-grade iron after the crash, and thus did become rich. The story of the ballet involves a greedy farmer who wants to make a goblin, a wizard to make it, a devil who brings it to life—the terrifying Kratt—a farmhand and the farmer’s daughter. Kratt ends up strangling the farmer. Tubin based the music on folk tunes, and in 1960 wrote a suite from the ballet. The score had been burned in the war, and Tubin gradually reconstructed it from the instrument parts and piano score he had managed to save.

The first Soviet occupation lasted about a year. June, 1941 became a month of horror as thousands of people were shot or deported to Russia. A week later, the German army approached and ignited a merciless civil war between communist supporters and the so-called forest brothers who had escaped the deportations and taken to the forests. At first, the German soldiers were thought to be liberators, but that was quickly disproven by their actions. Events everywhere were horrific; the Vanemuine concertmaster was shot, and one of the violinists later confessed in anguish to Tubin that he had been in the firing squad.

Adaptation

Eduard Tubin and his family lasted out the first Soviet occupation and the German occupation hoping that things would change. Eventually the lack of political freedom, the stifling of creative artistic expression, and the hardships and danger of everyday life became too much. The deportations at the end of the first Soviet occupation were a clear message that it was time to leave. As the Soviets moved in, thirty thousand people fled in panic. There was a break in the weather; 600 people crowded onto a 250-person ship, the Triina, in the Tallinn harbor. Eduard Tubin, his wife and two sons were among them. With a backdrop of black smoke as Tallinn burned, the ship left port on Sept. 20, 1944. The engine failed, and they drifted in the Baltic Sea for two days until the Swedish coast guard spotted them and towed the Triina to an island near Stockholm. Thus did a new life begin. Back at home, musicians were soon subjected to show trials, scores were burned, and books; Tubin’s friend, the violinist Evald Turgan, was sent to Siberia.

Many musicians and artists had managed to escape; on the Triina alone were Olav Roots, Juhan Aavik, violinist Zelia Aumere, and others, singers and writers. In the quarantine camp, despite all the problems of illness and disease, the exiles began to organize concerts and shows, with Tubin accompanying on piano. He started working with the Estonian YMCA Male Choir and continued for many years. Soon a solution to the problem of making a living was found. Musicians and artists who could not be sent to work in the forests or the textile mills were given archival jobs in museums and libraries. Those jobs were not always up to their training and talents, but for many they were a blessing.

Drottningholm Theater

Tubin was assigned to the library of the beautiful 18th century Drottningholm Theater at Drottningholm Palace, the residence of the Swedish royal family. The theater had fallen into disuse, but it was to be restored and revived. Digging into music libraries, Tubin found forgotten masterpieces. The director agreed that his work would be to restore the old scores and write orchestra parts, working at home. During the other half of the day, he could write his own music. The director got an expert, Tubin got a salary and time to write, and he continued at the job for almost 30 years until his retirement in 1972. Among the wealth of restorations he produced was the orchestration of a complete Haydn opera from the piano score. He also free-lanced for the Stockholm Opera and the Stockholm Concert Society, both of which always needed copyists and orchestrators. The family found an apartment in a southern suburb near a nature reserve, began to learn Swedish, and got on with their new lives.

Those first years in Sweden were productive ones for Tubin’s own work, and marked a change in his music. His son Eino writes: “The earlier romanticism and lyricism gave way to a direct no-nonsense tonal language with strong rhythms that could sometimes even feel aggressive.” An early success was the Symphony No. 5, which during Tubin’s lifetime became his best known composition. It was performed in late 1946 in Stockholm. The critic and composer Moses Pergament was impressed: “. . . sovereign mastery of musical form . . . not restricted by a program . . . creates with strict musical logic . . . a musical depiction of Estonian national tragedy . . . uplifting but also soothing and liberating.”

The family began traveling occasionally. On a trip that he unusually took alone, to Bayreuth, Tubin described with some amusement the audience members listening to Wagner wearing tuxedos, while the orchestra members in the deep pit were wearing Bavarian leather shorts. He didn’t completely appreciate the presentation of the operas as the singers mostly stood still and gestured. For himself, his real love was symphonic writing, but in time he acquired a thorough understanding of the challenges of opera.

Estonia Beckons

When Khrushchev came to power, the communist government began to allow limited contacts with the outside world. Tubin’s music had been banned in Estonia from 1948 to 1956; now the ban was lifted. Emissaries from the Soviet embassy began to visit him every year, trying to persuade him to come back for a visit. He got access to scores that he hadn’t seen in 14 years, and others were smuggled out on film. The Estonians’ first wish was that the score of his ballet Kratt should be restored. It was staged in Tartu in 1961 after a year-long restoration of the music—the composer having commented that it would have been easier to write a whole new ballet—and ran for an unprecedented 53 performances. Tubin by then had Swedish citizenship and reluctantly agreed to visit. The trip caused a certain amount of condemnation among some exiles, even among some of his friends like Olav Roots who was at that time conductor of the Columbian symphony in Bogota. But soon it became relatively common for exiles to travel to Estonia. The puppet regime, of course, was really after his permanent return to Estonia, to give them some respectability. Tubin later wrote Roots that one of his purposes in going had been to bring “a breath of fresh air” to his younger colleagues in Estonia, and that he had not hesitated to reveal himself as a free-thinking person of western orientation. He felt that the composers had as a result of his visit all assimilated something of his work, whether rhythm, development of motifs, or formal nuances. The Estonia theater was allowed to commission two operas from him. Barbara von Tisenhusen was a success, but with the second opera there was trouble later as the authorities found unsuitable the original story’s character of a cuckolded priest. Ready in 1971, The Parson of Reigi was properly performed only in 1988. Meanwhile, the Soviet regime cooled considerably as they realized Tubin would not return to Estonia, and his music was again banned until after his death, and freed in the time of Gorbachev.

Aftermath

After decades of steady, productive work, Tubin began to struggle with what proved to be a long illness, although he had a number of good years after retiring from Drottningholm during which he was still able to travel. He died in Stockholm on November 17, 1982. His last trip abroad had been to Boston for the centenary concerts in 1981, where his Symphony No. 10 was performed several times. Their old friend Neeme Järvi took the Tubins under his wing on that occasion and they even visited childhood friends. It was a special trip, more so as Tubin had once said that “the best times in my life are when my music is played and I can be there myself.” A special evening at the Estonian House in New York City was held in his honor, perhaps a kind of apology for the criticism of his trip to occupied Estonia two decades earlier. It is not unlikely that Evi Liivak was among the guests, since she and her husband lived there. In May of 1982, he was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Music Academy, a great honor, along with Isaac Stern and Sergiu Celibidache. Sadly, by November he was in hospital for the last time. Neeme Järvi had long been interested in recording a complete symphony cycle. To Tubin’s joy, his friend called the hospital from London and promised that it would happen. It did, over the next ten years.

What did Eduard Tubin think about his time in Sweden? He had spent half his life and two-thirds of his creative life there. In a 1970 letter to Olav Roots, he wrote: “I could add that I am officially a “Swedish composer,” I am on the best, friendly terms with them, but nobody yet accepts me as a real Swede. The radio here is rather reluctant to play my things, I get always more royalties for my works from abroad than from Sweden, but life still is rather good, it could be worse . . .”

Even after he acquired Swedish citizenship, the Swedes remained ambivalent as to his position in their musical life. In fact the extensive traveling had made him a cosmopolitan, one who carried a treasury of Estonian folk melody in his mind and had used it to wonderful advantage. In 1979 he showed his humor and lack of self-pity when a radio journalist tried to provoke him by asking if he didn’t feel bitter having lost the status he had in Estonia:

ET: Yes, but dear me, what does it help! It doesn’t help at all. In the beginning I had of course a great homesickness. Everything that I had there was left behind, and now I’m sitting here rewriting some old baroque music! But I could overcome this.

SH: How did you overcome?

ET: Occasionally I had a shot of vodka and it made me merrier . . .

A Few Words on Style and Program Music

Sometimes it is assumed that music reflects the state of the world around the composer at the time it was written. In Tubin’s case at least the opposite seems to be more accurate. The Violin Concerto No. 1 and the Symphony No. 4 are lyric and intimate, although written soon after the German occupation and the heavy street fighting in Tartu. Later this seemed to happen in reverse: as things were going well in Sweden and life was quite good, compositions often sounded denser and more agitated. Perhaps the composer needed to find his inner calm during a crisis, and when things were quieter externally, felt more able to express some of the emotional impact of previous events.

Program music, the concept of a piece of music designed with a preconceived narrative or to evoke a specific idea, was a subject that Tubin thought about. His views were somewhat ambiguous. He liked descriptive works such as Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition and loved Disney’s Fantasia. He had, after all, once been a movie musician. He obtained a copy of the Grand Canyon Suite at a time when it was difficult to do so in Sweden. The question was whether something could be described entirely by music. Later in life he always argued against this idea, and would use as examples pieces of music that could be interpreted in very different ways. He wrote to the choral composer Veljo Tormis in 1975 that he had thought a lot about Stravinsky’s (1930) statement that …”music is, by its very nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all…” Tubin wrote to his friend that he had ruminated on the subject:

“I have tried as a test to listen to all kinds of programmatic music, until I at the end understood that it has nothing to do with creating an image according to the text. At most there can be a kind of music, which after reading the text evokes a mood that is in accord with that of the text— “a garden in rain,” “a peaceful evening,” “thunder,” “riding at night” etc. If you don’t have the program handy, it will be highly questionable what the composer wanted to show; but if the inner logic of the music is good and solid, then I hear this in the first place and feel happy about it . . .”

He maintained that his own music was “chemically free” of any programs. He did not normally give names to his music, but one exception is the Symphony No 2, Legendary, which he describes being inspired by the sea and the waves. According to his son, he was at that time also sketching Estonian freedom fighters and Teutonic knights for a new chess set. His friend, the musician Harri Kiisk, said that Tubin did not have a concrete program in mind and that the name gave an indication of the work’s character. The piano sonata Northern Lights may have been inspired by nature, but was not given its name by Tubin.

Several other comments relate to the Symphony No. 7. In an interview Tubin explained that there was no purely atonal music:

“There is always a tonal basis to stand on. But the tonic can change very quickly, be moved to different voices or just be there latently. If you do not follow your ear and artistic consciousness, you end up either making cliches or in a swamp.”

In the last movement of the 7th, he experimented with a covert 11-tone technique and was pleased with the result:

“The most difficult thing in modern music is to write a flowing allegro movement. Instead of tonal points of support, I have in this movement used a continuous melodic and rhythmic tension. The energy that drives the music forwards is stored in the fuel depot of the three main motifs. I am happy that I was able to write this movement.”

Tubin, caught in the political storms of the 20th century, persisted, and wrote wonderful music. He left us ten symphonies, part of an eleventh, other symphonic works, concertos for violin, piano, double bass, cello and balalaika, opera, ballet and choral works, and chamber music. If some Estonians in the 30s had thought his music too modern, and later some Swedes thought it too conservative, eventually reviewers and musicians understood that it is in a class of its own. His museum is in Alatskivi Castle, near Lake Peipus and the places of his boyhood, and there is an interactive light and sound memorial outside the Vanemuine Theater in Tartu. His election to the Swedish Royal Academy of Music could be described as his Swedish memorial. He saw himself as a professional who knew his trade, and stuck to his ideals in a changing world. He loved Haydn and his subtle humor; Stravinsky’s boldness, Bartok’s crispness; kept a signed photo of Prokofiev on the piano and a small picture of Mozart on the wall.

©C. Sminthe 2016

[hr]

Sources

Detailed information about Eduard Tubin is not yet easily available in English. Grateful thanks to Eino Tubin for allowing the use of the English draft of his unpublished biography of his father, Eduard Tubin. Versions have been published in Swedish and Estonian.

Rumessen, Vardo, The Works of Eduard Tubin, ETW, Gehrmans Musikförlag, Tallinn/Stockholm, 2003. A catalog of all works with relevant information.

Tubin, Eino, The Professional, Yearbook of the International Eduard Tubin Society, 4/2004.

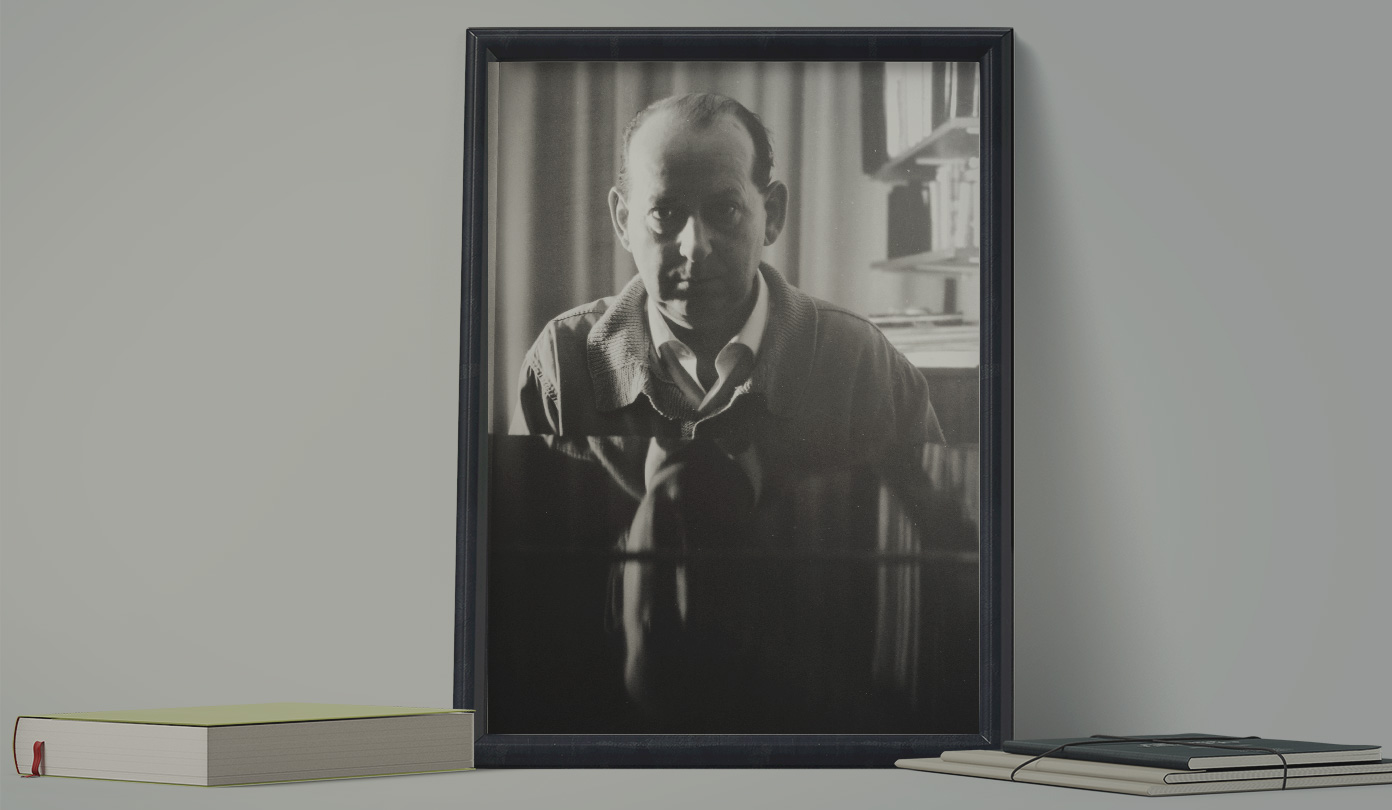

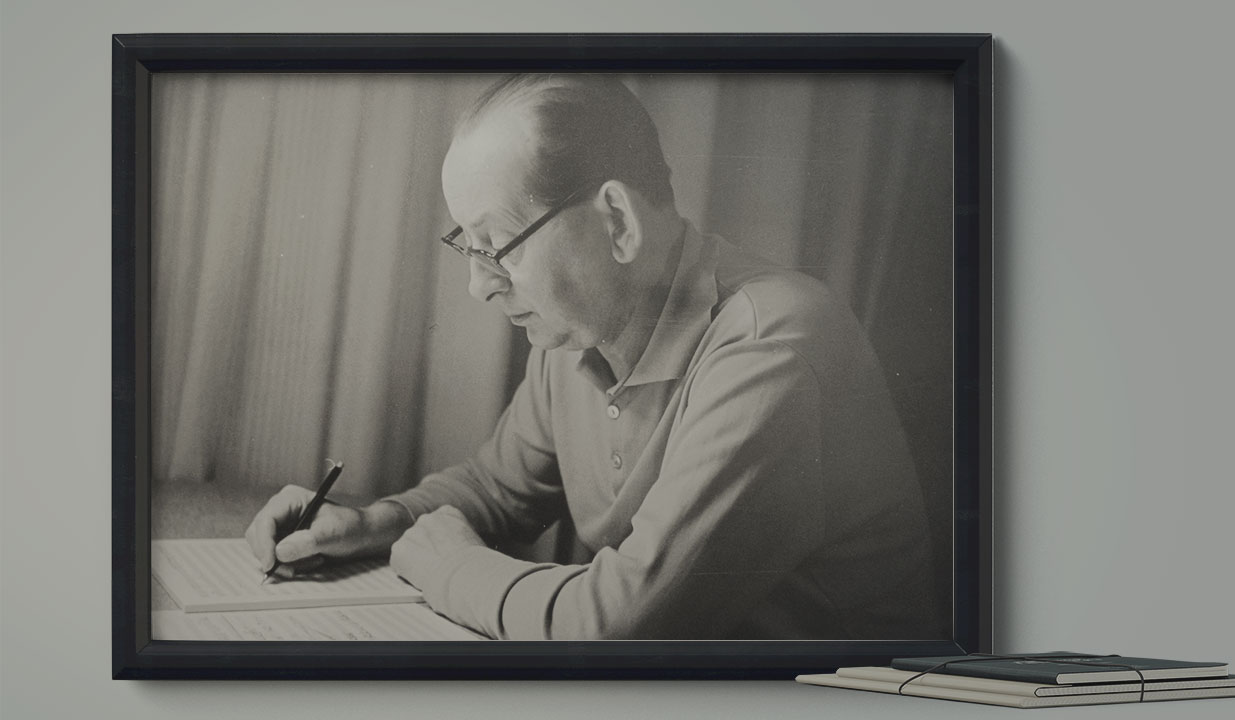

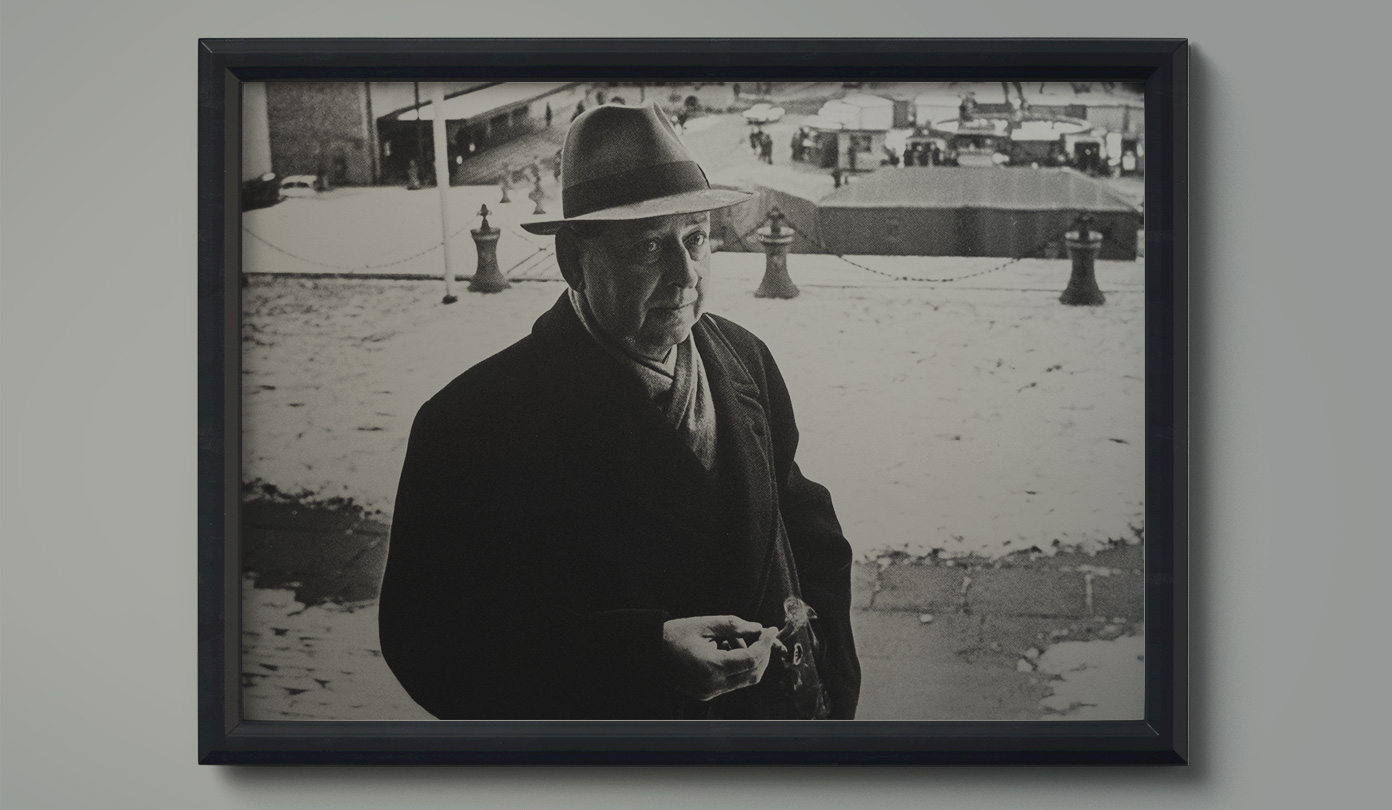

Photos courtesy of Eino Tubin.